In 1892, the Financial Times was struggling.

They had started the newspaper a few years ago.

And they were competing against other newspapers that covered business and finance news.

The shark in the pond was Financial News.

But the Financial Times team believed they had better content than them.

They didn’t just cover the news.

They provided insights into what those events mean for the economy.

Yet, their conviction about content quality didn’t convert into more sales.

So they faced the risk of going out of business.

But one day, an unexpected idea came up.

One of the Financial Times editors was passing by a store.

Dozens of newspapers were hanging one next to the other.

His eyes intuitively tried to find his own newspaper.

But it took a few seconds to identify Financial Times in the sea of white papers.

That made him think.

They worked hard every day to provide useful financial insights to readers.

Yet when people went to a newsstand to choose a newspaper, it was almost impossible to identify the Financial Times among others.

So when he arrived at the office that day, he proposed an idea to his colleagues:

“Let’s change the color of our paper.”

Some of his colleagues found the idea ridiculous.

But they decided to give it a shot as the newspaper was failing anyway.

They asked the printing company about different paper colors.

Almost all of them were more expensive than white.

But there was one cheaper color as it was unbleached paper: salmon pink.

So at the beginning of 1893, the Financial Times was printed on pink paper for the first time.

The result?

Just as the editor expected, the Financial Times stood out among all white newspapers.

People who visited stores noticed it.

So sales spiked.

Plus, people started associating the distinct salmon pink paper with the Financial Times’ unique insights.

Financial Times was already different with its content.

Now it was also distinct with its salmon pink color.

And in 1945 after 57 years of rivalry, Financial Times merged with Financial News under the Financial Times brand.

Today it’s more expensive to print on salmon pink paper.

But Financial Times keeps the tradition that made the brand distinct.

Distinct gets into the mind… And stays there

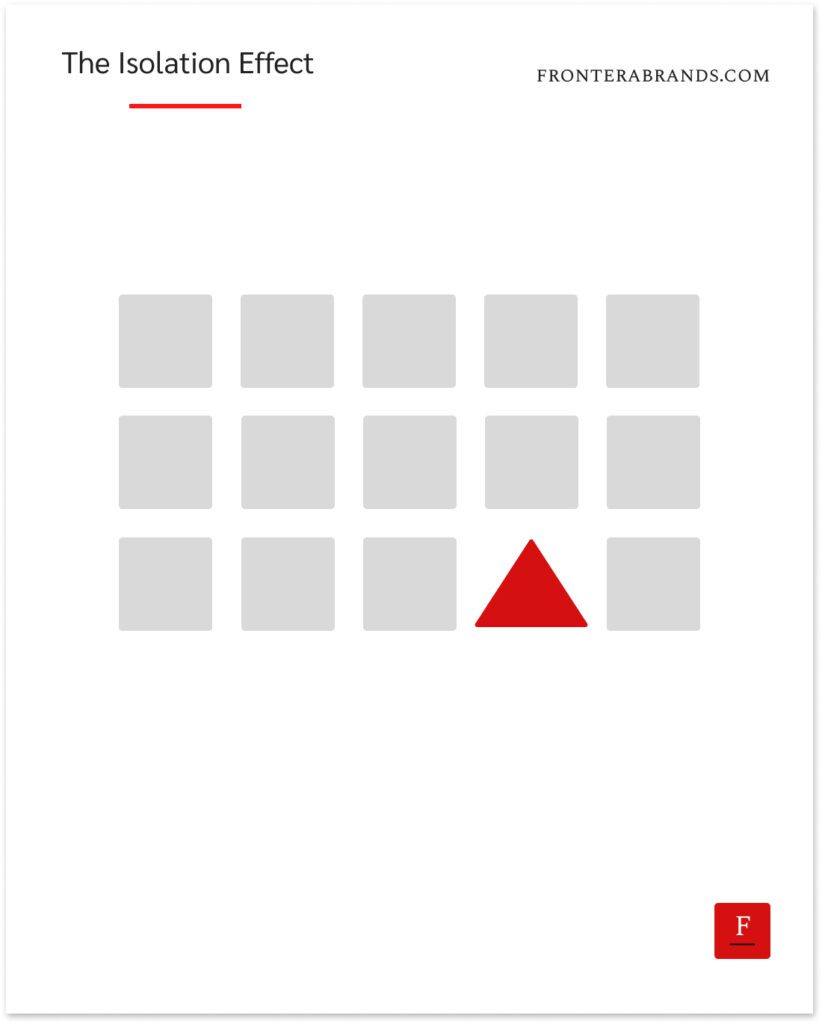

In 1933, German psychiatrist Hedwig von Restorff made an experiment.

Imagine a shopping list.

Let’s say you wrote all items in black, but “watermelon” in red.

He found out that people remembered the visually “isolated” item —in this case watermelon— more than the others.

He called this the Isolation Effect.

Later von Restorff and other researchers realized the Isolation Effect applies even to auditory, verbal, and semantic (meaning) stimuli.

So distinct visuals, distinct tone of voice, and distinct messages are more memorable.

Hence they allow brands to build mental availability.

Financial Times’ story is a good example.

Once it became salmon pink, people paid more attention and remembered it more than the others.

It stuck in their minds.

The Isolation Effect has an obvious consequence.

If you want your brand to be memorable, you have to make it distinct — visually and verbally.

So you can get into prospects’ minds, stay there, and drastically increase your chances of a sale.

Now the question is how can you make your brand distinctive?

It’s a huge topic on its own.

But here are three tips to “isolate” your brand from competitors:

1. Get away from the “default” of your market

In Competition Analysis, we’ve talked about how you have to understand the competition first to know what you have to differentiate against.

It applies here too.

First, you have to understand the default settings of your market.

Like using navy blue for a financial services company because it represents trust.

Like using a formal tone of voice because it’s B2B.

Or messaging on the same problems and benefits only because that’s what everybody else is doing.

It’s tempting to adhere to default.

It feels safer.

But that’s the definition of blending in.

So understand your market’s clichés first.

Then go against them to become distinct.

Remember Cross-Industry Innovation.

You know what Picasso said:

“Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

2. Be bold

In 2007, British confectionery brand Cadbury was having a terrible year.

They had to recall their products due to a bacteria exposure in one of their factories.

Plus, people found out their chocolates had traces of nuts without nut allergy warnings.

And they had to cut 7,500 jobs.

So, the public’s perception of Cadbury was negative.

To turn things around, they partnered with a new agency (Fallon).

And Fallon kicked off the campaign with an iconic ad.

The gorilla was listening to Phil Collins’ legendary “In the Air Tonight” song.

But as the camera zoomed out people started seeing he also had a drum set in front of him.

And he was waiting for the drum fill.

So when the moment came in the song, he played the drums.

After all this, a package of Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate appeared on the screen with its tagline “A glass and a half full of joy.”

Ridiculous idea.

But it turned around Cadbury’s public perception and increased its sales after months.

The ad was bold and distinct.

So it worked.

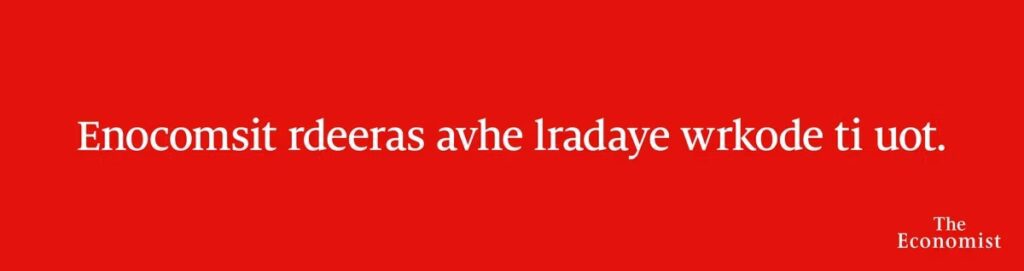

Here’s another example from the news media.

The Economist is famous for their campaigns that show how their readers are elite and smart.

Look at this one:

Takes a few seconds to figure out.

But it’s distinct.

It’s bold.

And it puts The Economist’s message in your mind.

So where am I getting at?

Even when executives know they have to isolate their brand in the market, they struggle when it comes to action.

Because it’s easier said than done.

Because it requires boldness.

It requires saying yes to ideas that make you a little scared to act.

So when you get the opportunity to stand out, act despite that fear.

Remember, fortune favors the bold.

3. Combine differentiation with distinctiveness

We often talk about the importance of creating a different value for customers.

But here’s the thing.

Even if you provide a different value in your market, if it doesn’t appear that way, customers won’t get it.

Just like what happened with Financial Times before they switched to pink paper.

They had the same differentiated product with their unique insights.

But people didn’t see it that way.

So Financial Times couldn’t get into readers’ minds and occupy a space.

Many founders and executives make this mistake.

They believe a better product/service alone can solve all the problems.

But it’s not enough.

You have to combine differentiation (your product/service’s unique value) with distinctiveness (how “isolated” your brand looks and sounds).

That combination makes winning brands.

A different value, communicated to the prospects with a distinct verbal and visual identity.

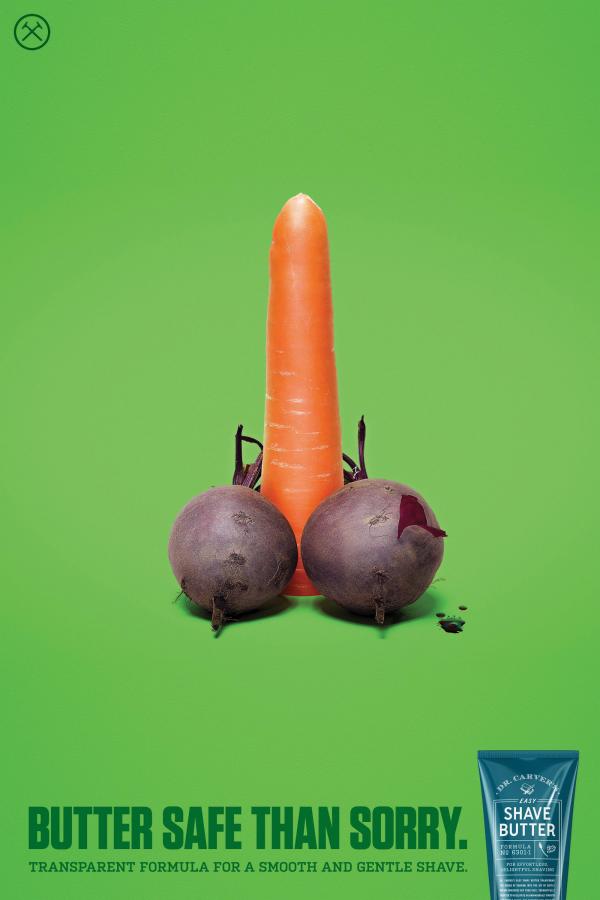

Dollar Shave Club is a brand that combines both perfectly.

They were different — because they provided cheap razor blades with a subscription.

They were distinct — because their tone of voice was humorous.

So among all the large brands that used the same old messages like “smooth” or “effective” razor blades with a serious tone, Dollar Shave Club got attention.

And they ended up getting acquired for $1 billion.

So think about your business.

You might have a great product or service.

But how distinctive is your brand’s tone of voice and narrative?

How distinctive is the message on your home page, social media, or ads?

Does it catch attention?

Does it make people stop and think?

Remember.

Communicating your value in a distinct way is as important as the value you create.

–

Enjoyed this article?

Then you’ll love the How Brands Win Newsletter.

Get the “7 Positioning Sins That Cost B2B Brands Millions” guide when you join. It’s free.