Bias for action is a mental error that causes us to act even when inaction is the best decision. First, let’s see how Coca-Cola executives made that mistake. And then how to avoid it to make better decisions.

In the 80s, Pepsi started its famous ad campaign on TV.

The Pepsi Challenge.

Pepsi made consumers go through a blind taste test between Pepsi and Coca-Cola.

And the majority preferred Pepsi.

They repeated the tests with different people in different places.

The result was the same.

Coca-Cola’s executive team freaked out after seeing the ads everywhere.

They hired researchers to do their own tests.

Pepsi’s claims were true.

All things equal, Pepsi’s sweeter taste was superior.

And now they were telling it to consumers everywhere.

The Coca-Cola executive team felt they had to do something as a response.

And decided to change Coca-Cola’s classic formula.

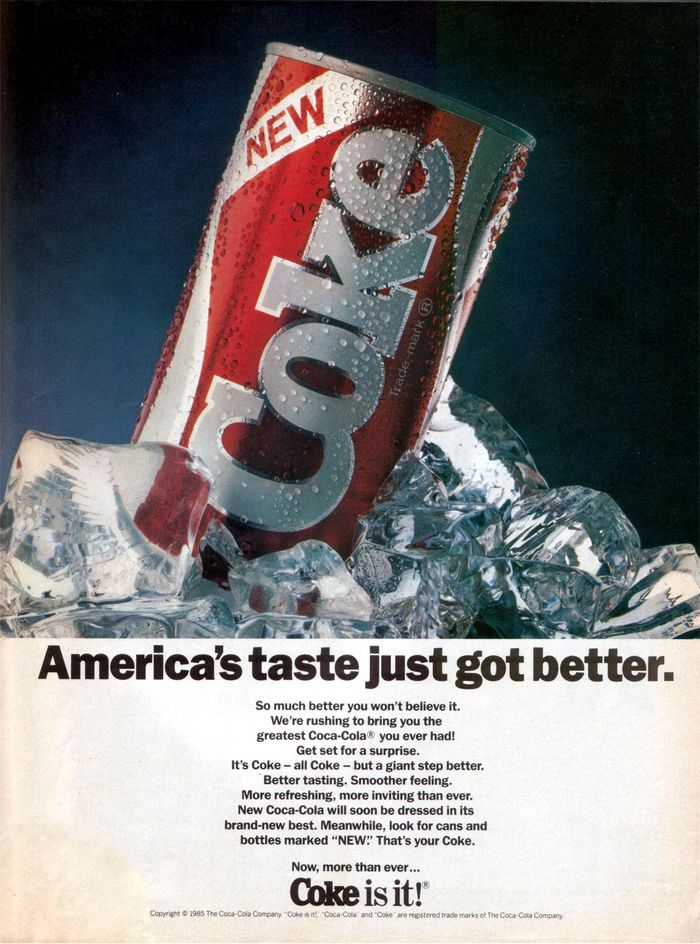

Coca-Cola announced the new coke with a big campaign.

Tests showed the new coke’s taste was better than Pepsi’s.

So the Coca-Cola team expected sales to explode.

But…

The public’s reaction was the opposite.

People hated the new Coca-Cola.

Coca-Cola started receiving 5,000 calls a day from angry customers to bring back the old formula.

People even protested on the street.

How dare they change the taste millions had been drinking for decades?

Sales started going down.

Coca-Cola couldn’t resist the pressure for so long.

And they brought back the old formula as ‘Coca‑Cola Classic’ 79 days later.

When actions become blunders

Now the story contains many lessons.

The first one is about marketing.

Yes, Pepsi Challenge showed Pepsi’s taste was better¹.

But it also proved the brand power of Coca-Cola.

When consumers saw the name, bottle, and red logo, the taste didn’t matter — as long as it was the classic Coca-Cola.

Another lesson from the story.

Coca-Cola executives felt compelled to take action after seeing Pepsi’s ad campaign.

So they reacted.

And broke something that was already working.

You know the fight or flight response when we feel in danger.

Our instincts tell us to act.

It’s an evolutionary behavior that has helped us survive for thousands of years — like the law of reciprocity we talked about last week.

But sometimes this tendency fails us in the modern world.

So people take action as a reflex without proper reasoning and make mistakes.

This is called bias for action.

Let’s see some more examples.

Bias for action examples:

- The harm caused by the healer: Doctors feel they must take action to cure a patient. So sometimes they make unnecessary treatments for non-fatal diseases. And they cause more harm than benefit.

- Speed without direction: People take some actions to feel productive. Like attending pointless meetings or handling unimportant tasks. Even though these actions don’t create value for anybody.

- Naive interventionism: Politicians intervene in complex issues where action brings unknown risks with little possible gain. And these adventures usually end up becoming failures. Like the US intervention in Afghanistan. Nassim Taleb calls it naive interventionism.

Now, action is good in most cases.

Especially when you start something from scratch and try to figure out how things work.

But as the stakes get higher, each uncalculated action can be costly.

Three tips to avoid bias for action:

1. Make inaction an option

Charlie Munger says the “sitting on your ass” investment style is his favorite.

As long as you own great businesses, you don’t need to worry about selling.

Time is in your favor.

So you can sit on your ass without doing anything.

This applies to other business decisions.

Inaction is always an option.

And sometimes it’s the best way forward.

So when you face complex problems, pause and consider if inaction could work better.

Remember, this is not inaction due to fear of failure or analysis paralysis.

It’s an intentional decision.

2. Ignore (most) opportunities

I know.

Sounds counterintuitive.

But bias for action often occurs with new opportunities.

When you have a certain level of success with a product or a business, you start having more and more opportunities along the way.

Sometimes new shiny projects, sometimes expansion to a new vertical.

It’s tempting to take on everything.

But our time (and focus) is limited.

So after you achieve initial success with a project, be selective with new opportunities.

That means saying no to good opportunities; to save your resources for the great ones.

Use methods like RICE scoring to take impact and probability of success into account to choose projects.

3. Never diverge from your strengths

Besides using resources, some actions also diverge you from your strengths.

For Coca-Cola, it was the classic formula.

And the emotion it triggered in people’s minds.

When they diverged, they failed.

Another example is when new CEOs make big acquisitions to leave a mark.

But most big acquisitions fail as they kill the focus of both companies.

So beware of actions that might diminish your competitive advantages.

Especially when you have them compounded for a long time (remember the flywheel effect).

Where everybody is taking action for the sake of action, use strategic inaction to stay on your path.

–

Enjoyed this article?

Then you’ll love the How Brands Win Newsletter.

Get the “5 Mental Models to Differentiate Your Business” guide when you join. It’s free.

Footnote:

¹About 20 years later, Malcolm Gladwell claimed Pepsi Challenge had a major flaw: people choose sweeter drinks when it’s only a sip. But they don’t like them as much when it’s a full glass.