In 2003, things were going great for Robert Brooks.

He bought the franchise rights for Hooters restaurant in the 80s and turned it into a successful restaurant chain with 430 branches worldwide.

The media mostly paid attention to Hooters Girls.

But restaurant businesses are tough.

Behind the attention-grabbing ‘breastaurant’ concept, Brooks built a well-functioning system to succeed.

But success brings its own problems.

Despite expanding the chain rapidly, Hooters still had too much cash.

So Brooks faced the inevitable problem that every successful business owner faces:

“How should we invest all this money?”

As he looked for potential options, an idea came to his mind — perhaps when he took a flight.

Hooters Airlines.

People —well, men— loved Hooters and the concept.

So bringing it to the aviation sector and making the flying experience more fun could sell a lot of tickets.

After all, Richard Branson had tried a fun airline concept with Virgin.

And that worked out well.

Plus, most airline valuations were lower after the September 11 attacks.

So Brooks decided that it was the right time to make a move.

And he bought Pace Airlines to rebrand it as Hooters Air.

The slogan was “Fly a mile high with us.”

Things started well for Hooters Air with all the media buzz.

But after a few months, reality hit.

The restaurant business was tricky, but aviation was even worse.

Regulations, high costs, low margins…

Hooters Air managed to provide a decent experience to its customers.

But that was not enough.

American Airlines and Southwest could offer better deals thanks to their operational efficiency and scale.

So Hooters Air customers didn’t stick around.

And unlike restaurants, Hooters had no experience or competitive advantage in aviation.

They were competing with giants in their own game.

So after three years of operation and a $40 million loss —which put even their restaurant business at risk— Hooters Air ceased operations.

Expansion done right

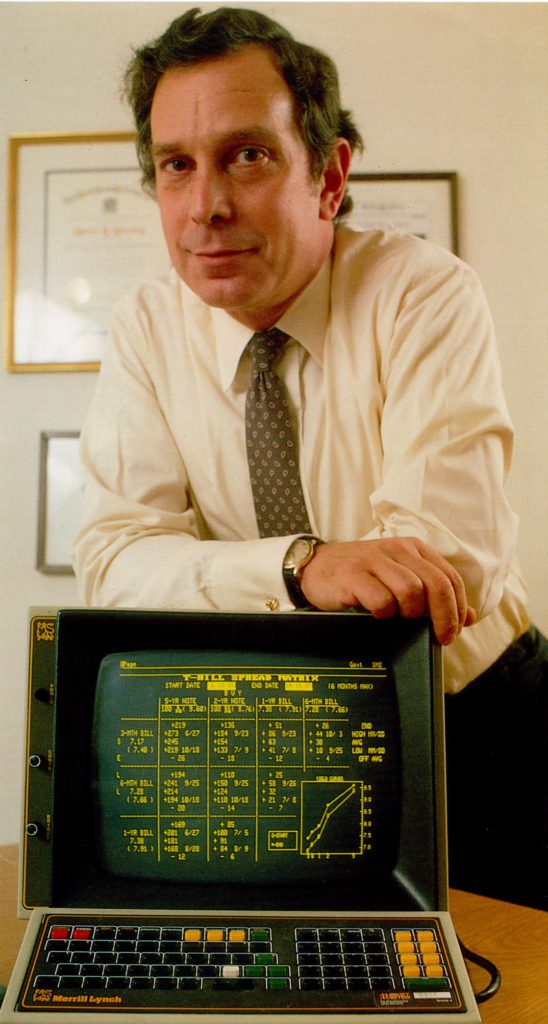

In the 80s, Michael Bloomberg faced the same problem as Robert Brooks.

After he got fired from Salomon Brothers, he started his own company to provide real-time data and insights to financial services companies.

At first, he called the product the Market Master Terminal.

But he quickly realized giving his name to the product would be better for marketing, so he changed it to Bloomberg.

Wall Street loved it.

And the Bloomberg Terminal became the norm in the financial world.

As it provided enormous value, Bloomberg could charge a premium — about $25k per user in today’s dollars.

So after a decade of growth, Michael Bloomberg was swimming in cash.

And he asked the same question: “How should we invest all this money?”

Well, maybe Bloomberg also thought about an airline.

But he was wise enough to do something else.

He knew Bloomberg’s core competency was data and insights.

And they had a perfect business model with the Bloomberg Terminal subscriptions.

So he realized the best investment would be something that would allow them to sell even more terminals.

How?

By going into media.

It was a genius move.

The media business was competitive.

But Bloomberg already had experience with data and insights.

So they were still playing their own game.

And unlike Hooters Air, Bloomberg didn’t even care about making a profit in the media business.

They already had a profit machine.

So media was only a channel to get more exposure and expand their core business.

In his autobiography, Bloomberg tells how the media leg supported the sales of terminals:

“Each news story is a product demo. More demos lead to more revenue. More revenue leads to more stories and then even more revenue.”

A perfect example of the flywheel effect.

And guess what?

The media expansion worked out so well, today Bloomberg has $12 billion in yearly revenue.

Most people know Bloomberg with its media business.

But about 95% of their revenue comes from Bloomberg Terminal.

And Michael Bloomberg still owns 88% of the company with a net worth of $90+ billion dollars.

Choosing games where the odds are in your favor

Two successful companies.

Two decisions.

And two different outcomes.

Now, if these decisions were bets, you could easily tell which decision had a better expected value.

Hooters Air was like an adventure.

The idea sounded cool.

But it was not the company’s competence.

And even successful airlines are hardly profitable, so the upside was limited.

But Bloomberg Media was the opposite.

Media was a new area, but it was still within Bloomberg’s competence.

And it didn’t even need to be profitable on its own to be a success for Bloomberg.

Little risk, and huge upside potential.

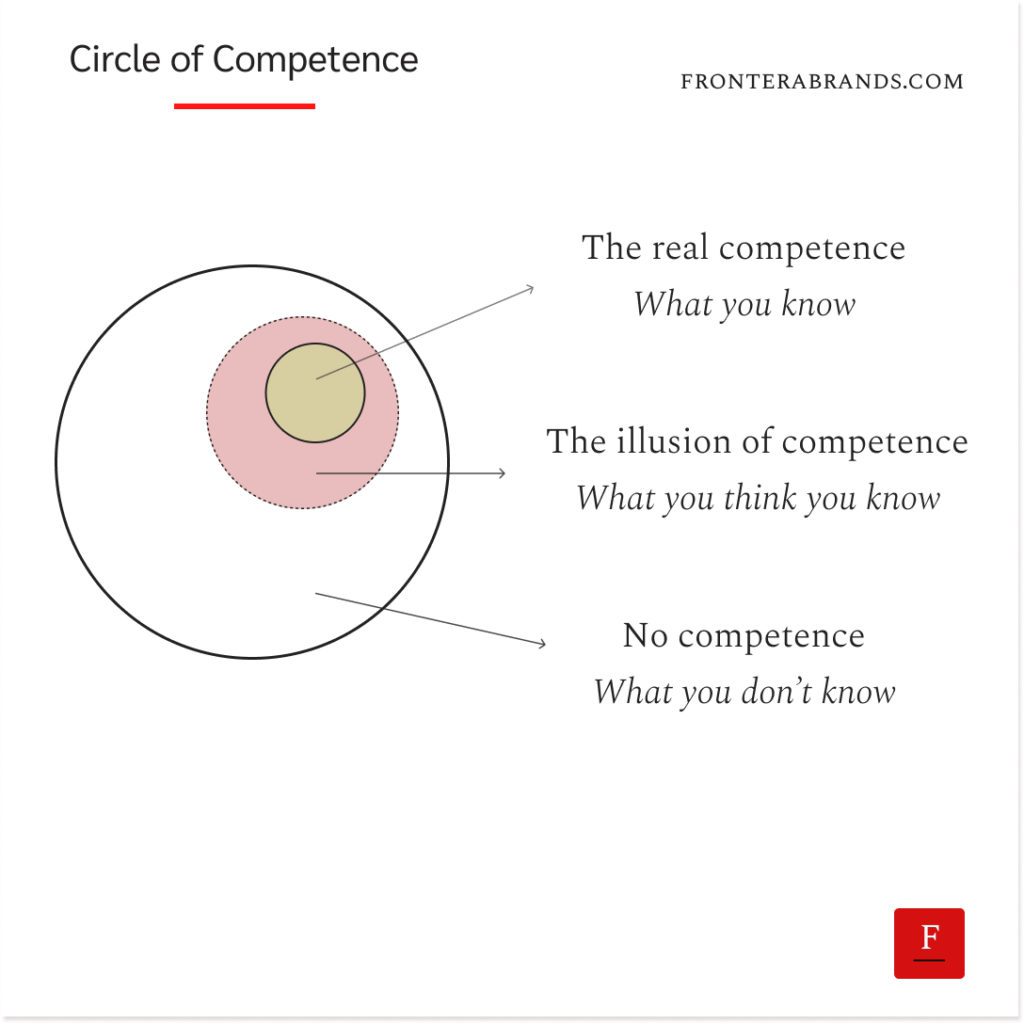

Warren Buffet explains the importance of knowing your competencies and making business/investment decisions accordingly in his 1992 Berkshire shareholder letter:

“What an investor needs is the ability to correctly evaluate selected businesses.

Note that word “selected”: You don’t have to be an expert on every company or even many.

You only have to be able to evaluate companies within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.”

And that might be the single most important factor in winning in business.

You play games where the odds are in your favor.

And intentionally avoid competing in areas where you don’t have an edge, no matter how tempting it is.

Two points to take advantage of your circle of competence:

1. Identify your core competencies

Buffett says the correct assessment of your circle of competence is more important than how big the circle is.

He is right.

Some businesses never realize where their true strength lies.

So they chase the wrong opportunities and dilute their resources on activities where they have no edge.

Another example from Bloomberg.

As its name suggests, Bloomberg’s intelligence product started as a “terminal” in the 80s.

Computers were rare and expensive.

So Bloomberg had to produce their own terminals and set them up in customers’ offices.

But as technology advanced, computers got cheaper, and new hardware companies entered the game.

What did Michael Bloomberg do?

He stopped producing his own hardware and partnered with hardware companies.

He knew Bloomberg’s competence was providing customers with data and insights.

Not producing hardware.

So when the game changed, he adapted.

And that reduced the complexity of his business and freed up resources for the core business.

His idea was simple.

Understand where your edge is and do everything you can to amplify it.

So answer this question:

“What are particular skills, knowledge, and expertise my business has that others don’t?”

And build everything around that.

Anything else is a waste of time and resources.

2. Operate from a position of strength

The stark contrast between the brand expansions of Hooters and Bloomberg shows us one thing.

Success in one area does not guarantee success in others.

So you should only expand into areas where you can leverage your strengths.

Why take a risk in a game where you don’t have any edge?

General Electric’s famous CEO Jack Welsh said it well: “If you don’t have a competitive advantage, don’t compete.”

Microsoft’s Teams expansion in 2017 is a good example.

Slack was a better product.

But Microsoft overpowered Slack by using its existing B2B offers and relationships.

Microsoft’s competitive advantage was so strong, it made other factors —like design, product quality, and even user opinions— irrelevant.

Today, Teams has around 280 million daily users while Slack has 30 million.

And Slack founders had to sell to Salesforce to stay in the game.

Obviously, not every company has big moats like Microsoft.

But it shows how much edge you can gain when you use your existing strengths.

So if you ever plan to expand your circle of competence, don’t start a new circle from scratch as Hooters did.

Expand into areas where your existing competencies will give you leverage.

That way, you’ll operate from a position of strength.

And you’ll stack the odds in your favor.

–

Enjoyed this article?

Then you’ll love the How Brands Win Newsletter.

Get the “7 Positioning Sins That Cost B2B Brands Millions” guide when you join. It’s free.