In 1983, Horst Schulze took on a big challenge.

He became a founding member and the president of The Ritz-Carlton Company.

The co-founders’ goal was clear.

Take the legacy of Ritz and Carlton names in the hotel industry.

And turn it into a successful luxury hotel chain.

But the hotel industry is one of those competitive sectors.

Many new businesses start, but not many last.

And a luxury brand where you have to justify rooms for thousands of dollars?

Good luck.

But Schulze had previous experience at Hilton and Hyatt hotels.

So he knew what he was getting into.

Ritz-Carlton had to have what other luxury hotels offered as a start — great facilities, service, and location.

But he also had to find a way to differentiate for Ritz-Carlton to last.

“Ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen”

So Schulze decided to question the basics.

What would a customer look for in a hotel?

What was the real desire?

He commissioned research to find an answer.

And after hundreds of interviews and surveys, one thing came up repeatedly.

Unlike many thought, people didn’t like hotels.

They had to stay in one as they were traveling, but deep inside they always looked for the comfort of home.

And not any home.

The home they had when they were kids — a safe, comfortable space where everything was taken care of by their mother and father at that moment.

And where they get a little spoiled with surprises.

Now, this insight might not mean anything to many people.

But Schulze had spent enough time in the hotel industry to know what to do with it.

So he empowered all employees to solve any customer issue or improve their experience when they see a chance without getting any approvals.

And he authorized a $2,000 per employee per guest budget for this.

This rule became famous as “the $2,000 rule” in the hotel industry.

And it created many legendary stories.

Like when a Ritz-Carlton employee flew from Atlanta to Hawaii to return the computer a guest forgot before a big speech.

Or when Ritz-Carlton employees dove to rescue the camera that a guest lost in the sea (they used this story in a campaign saying “memories rescued”).

But besides creating interesting stories, this exceptional service truly differentiated Ritz-Carlton from others.

And it became one of the best luxury hotel brands in the world.

Schulze codified Ritz-Carlton’s philosophy with a mantra:

“We are ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen.”

When details build the brand

Here’s the thing.

Some other hotel chains had more luxurious facilities.

But they didn’t become as successful as Ritz-Carlton and became synonymous with the word “luxury” in the hotel industry.

Why?

Well, trying to solve customer problems is a given in luxury service.

But all big companies have processes.

So employees might ask managers, get approvals, and sometimes lose hours before fixing a problem.

But at Ritz-Carlton, it was instant.

Any employee had the authority (and the budget) to solve a problem or delight a customer with a surprise.

This didn’t only cause customers to be happy with the service.

But it also affected how they see the other aspects of the brand.

And that’s called the Halo Effect.

A Reddit user tells how a Ritz-Carlton waiter inviting a guest to a $600 tab caused the guest to take his business conference —which was worth hundreds of thousands of dollars— to Ritz-Carlton.

Perfect example.

It applies on a personal level too (psychologist Edward Thorndike coined the term).

When you meet with a good-looking person who speaks with confidence, you intuitively believe that person is competent in what he or she does.

Even if you have no idea about the actual competency.

So, how can you benefit from the Halo Effect for your brand?

Two ways to use the Halo Effect for your brand:

1. Chase excellence

After his extraordinary success with Ritz-Carlton, Schulze wrote a book to share his wisdom.

The book has many business lessons and stories — including the ones we talked about at the beginning.

You know the title he gave to the book?

“Excellence wins.”

And excellence means not only doing a good job but obsessing over every detail.

Like how you onboard a client, the copy on your website, or the design of your product…

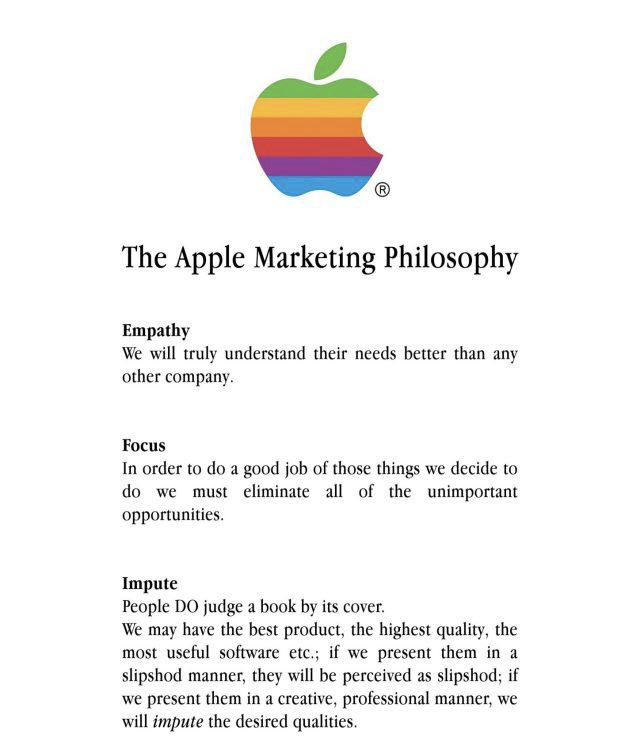

Another company that has chased excellence since its early days is Apple.

Back in 1977, Steve Jobs & Mike Markkula wrote Apple’s three marketing principles.

The first two principles were empathy and focus.

These words need no explanation.

But the last one triggers a question mark in your mind.

Impute.

It said:

“People do judge a book by its cover. We may have the best product, the highest quality, the most useful software, etc.

If we present them in a slipshod manner, they will be perceived as slipshod.

If we present them in a creative, professional manner, we will impute the desired qualities.”

Based on this principle, Apple has been paying attention to all the details of its brand.

The packaging of iPhones, the design of its stores, and new product presentations…

Because they knew people judged a book by its cover.

And they still know details are not trivial.

Details are the brand.

So chase excellence.

The extra resources you spend on details might look unnecessary at first.

But over time, that becomes the difference between an average brand and a great one.

2. Keep a narrow front

The Halo Effect has a sister.

And it causes the reverse.

When we notice something bad about a brand, that builds a negative bias about all the other aspects of that brand.

It’s called the Horn Effect.

Now here’s the thing.

When you have more products and services, you increase your chances of doing an average job.

Because the more things you do, the less expertise you have.

You broaden the front.

And you risk customers and clients judging your brand by that average work.

It’s a recipe for failure.

How do we judge Apple?

By the amazing (and only a few) personal devices they build.

But Samsung?

Maybe you bought a Samsung microwave.

You opened that big ugly brown box full of foam and bubble wrap to put it in your kitchen.

And it started making weird noises after a month.

This does not only affect how you see Samsung microwaves but also the Samsung brand.

And then their executives question why they don’t have pricing power.

By the way, the same happens in services too.

The more services you offer for more customer segments, the less valuable you become for each.

Remember brand dilution.

And always keep a narrow front.

In crowded markets, only specialists win.

–

Found this article useful?

Then you’ll love the How Brands Win Newsletter.

Get the “5 Mental Models to Differentiate Your Business” guide when you join. It’s free.