In 1982, programmer John Walker decided to make a big bet.

His friend Michael Riddle had a computer-aided design (CAD) program that he struggled to sell.

But Walker believed in the idea.

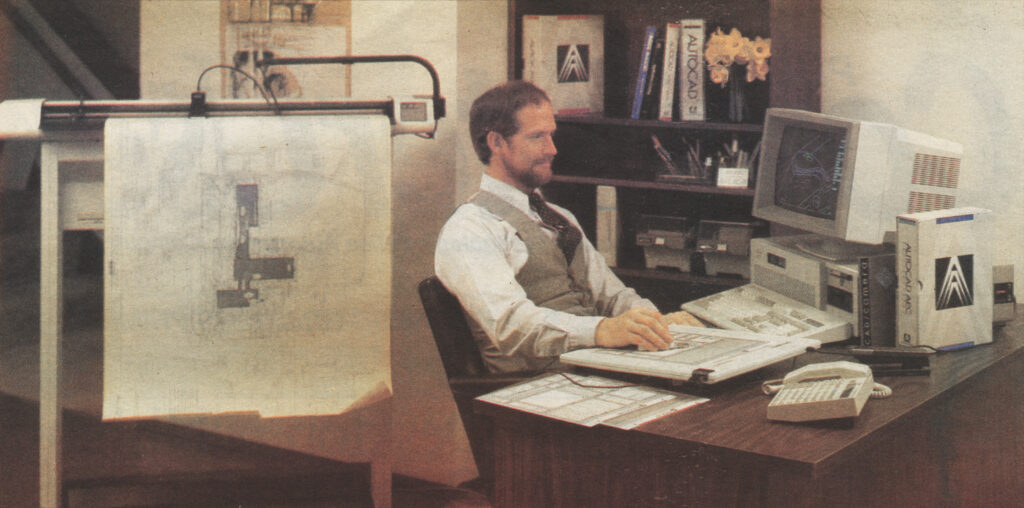

Designers who worked on complex projects —like engineers and architects— needed precise measurements.

And doing that on paper was painful.

You had to use rulers and carefully draw everything for days.

Realize you have to change something?

Good luck.

It’d take ages to erase, make new calculations with calculators, and draw again.

At the time, computers were just starting to get popular.

And there were some CAD programs on the market.

But they were super expensive.

Because most of them were sold by computer manufacturers.

That meant designers had to buy their mainframe computers to use those programs.

And most designers couldn’t afford them.

So designing by hand was painful.

And buying a CAD program was out of budget.

That’s why Walker believed Riddle’s program had a lot of potential.

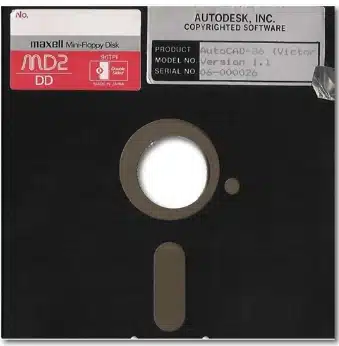

It didn’t require any proprietary hardware — it worked on all personal computers.

Hence they could price it at one-tenth of other programs.

So Walker co-founded Autodesk with other programmers and acquired Riddle’s software.

They made some improvements to it.

And they named it AutoCAD.

The first version of AutoCAD went on to the market the same year.

AutoCAD had all the giant computer manufacturers as competitors.

But those manufacturers didn’t want to make inexpensive software.

Why?

Because that would mean disrupting their own hardware sales.

So designers quickly adopted AutoCAD thanks to its attractive price point.

And only in a few years, it became the default CAD tool all around the world.

Computer manufacturers realized the opportunity they had missed.

But it was too late.

Fast forward to today.

Today AutoCAD has more features.

And Autodesk has a range of products alongside AutoCAD.

But what the company stands for hasn’t changed in 40+ years.

They still solve specific problems for a niche audience: designers who work on complex designs.

They kept improving their products and providing new capabilities to those designers.

99% of people in the world probably have never heard of Autodesk or its products.

But today, they have a $5 billion revenue and a $60 billion market cap.

Going narrow doesn’t mean going small

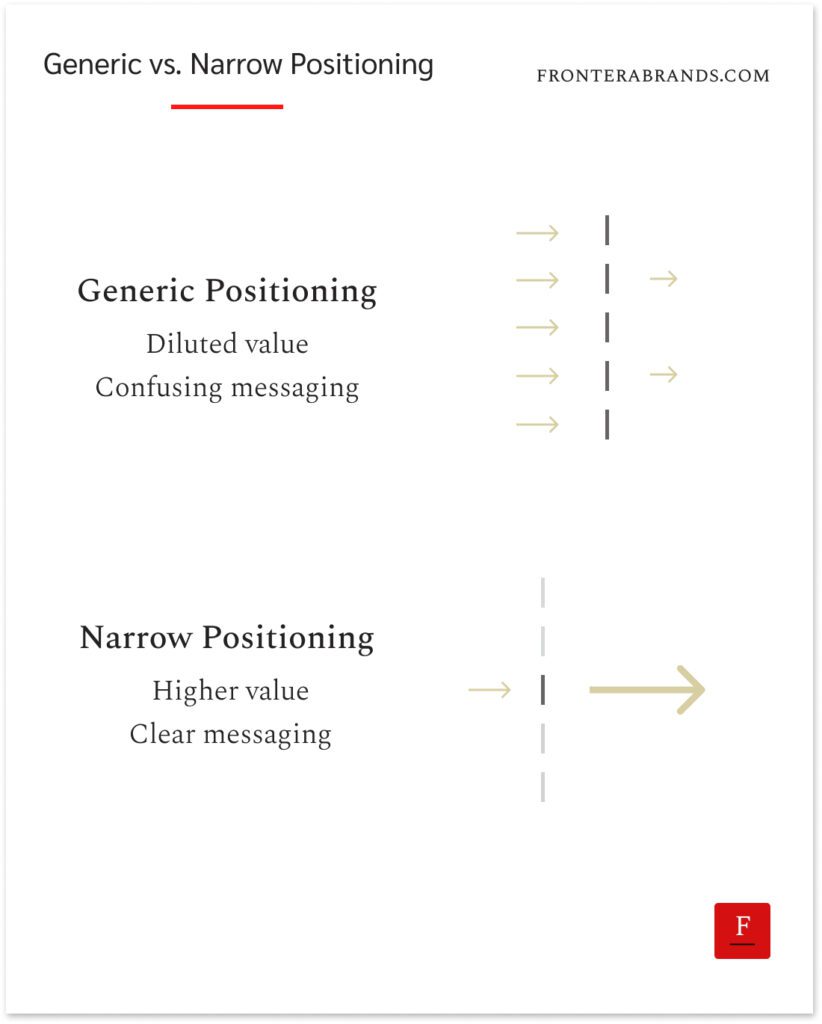

Some founders and executives believe in a common fallacy.

They believe if they narrowed their brand’s focus, it would limit their growth potential.

They fear missing out:

“What about all these other customers we can help?”

“What if other customers come to our website and see that we don’t serve them?”

They feel like they would say no to “free revenue.”

So they refuse to get specific on the problem they are solving.

They refuse to get specific on who they solve it for.

And guess what happens?

Their positioning ends up being too generic.

Hence their message doesn’t resonate with any customer segment.

They can’t even build a decent product/service as they try to be everything to everybody.

So their businesses struggle to grow.

That’s why Autodesk’s story has a good lesson.

AutoCAD solved a specific problem for specific customers.

And they got deeper and deeper into the same area, instead of jumping into other customers or business lines.

They grew by reaching more of the same customers who wanted to solve the same problem.

Yes, it’s counterintuitive.

Going narrow seems like going small at first.

But it actually increases your chances of growing much faster than a generic brand that tries to solve many problems for many customers.

Because when you make a choice and stay focused, you build expertise.

You start seeing opportunities that no generalist can ever see.

And it becomes much easier to explain what you do and who you do it for.

Blair Enns makes a nice analogy to describe this.

Imagine three doors in front of you.

You have to choose one.

And they are irreversible — once you pass through one, you can’t go back.

So the decision stresses you out.

Because you worry about the opportunities behind the other doors.

But actually, it shouldn’t be a difficult choice.

What most people don’t know is once you choose a door and pass through it, new doors appear.

Deeper problems, bigger opportunities…

Hence by sacrificing other doors, you increase your chances of winning big.

So for those who believe going narrow means limiting the company’s growth potential, you can ask this question:

Is a $60 billion market cap big enough?

–

Enjoyed this article?

Then you’ll love the How Brands Win Newsletter.

Get the “7 Positioning Sins That Cost B2B Brands Millions” guide when you join. It’s free.